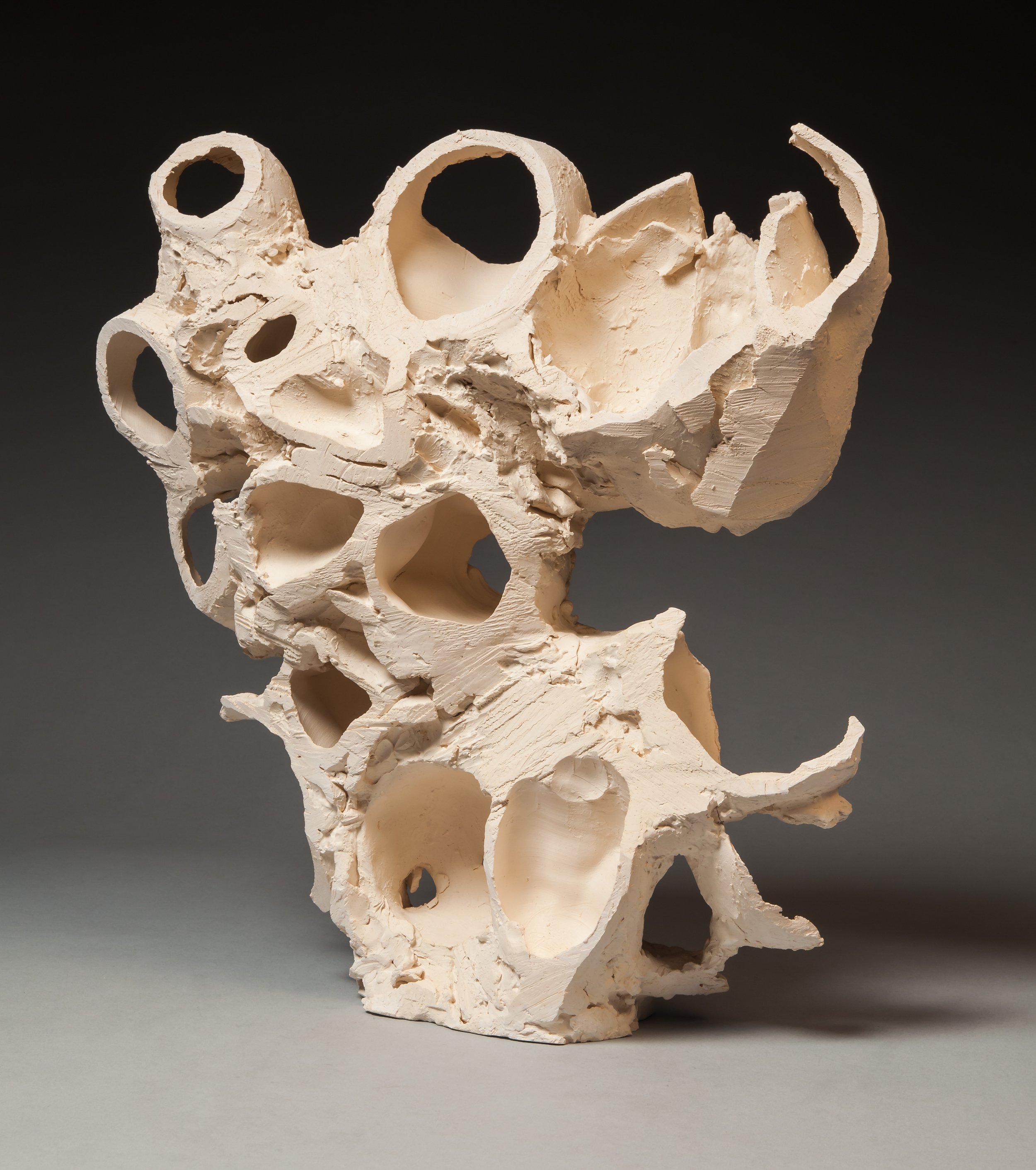

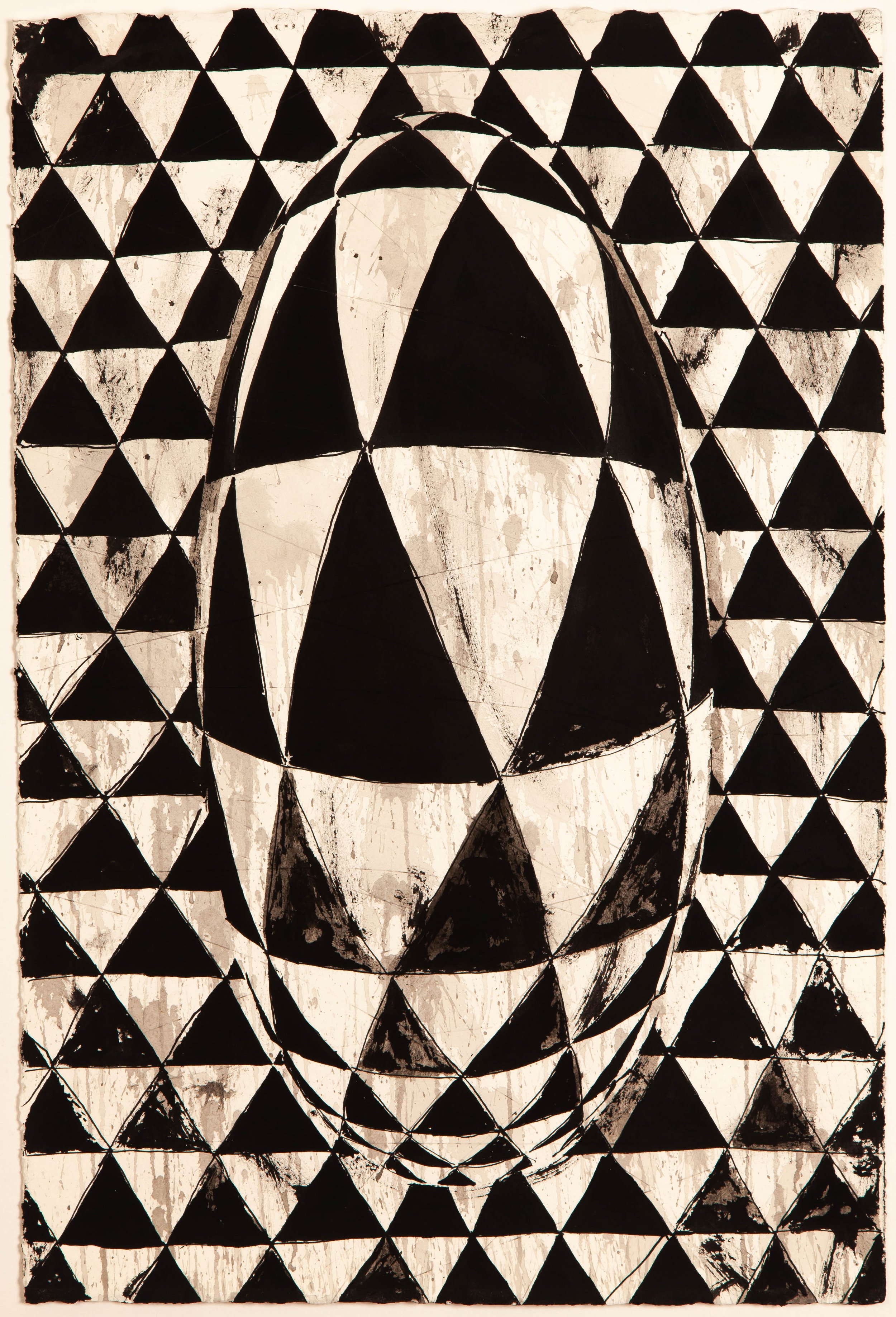

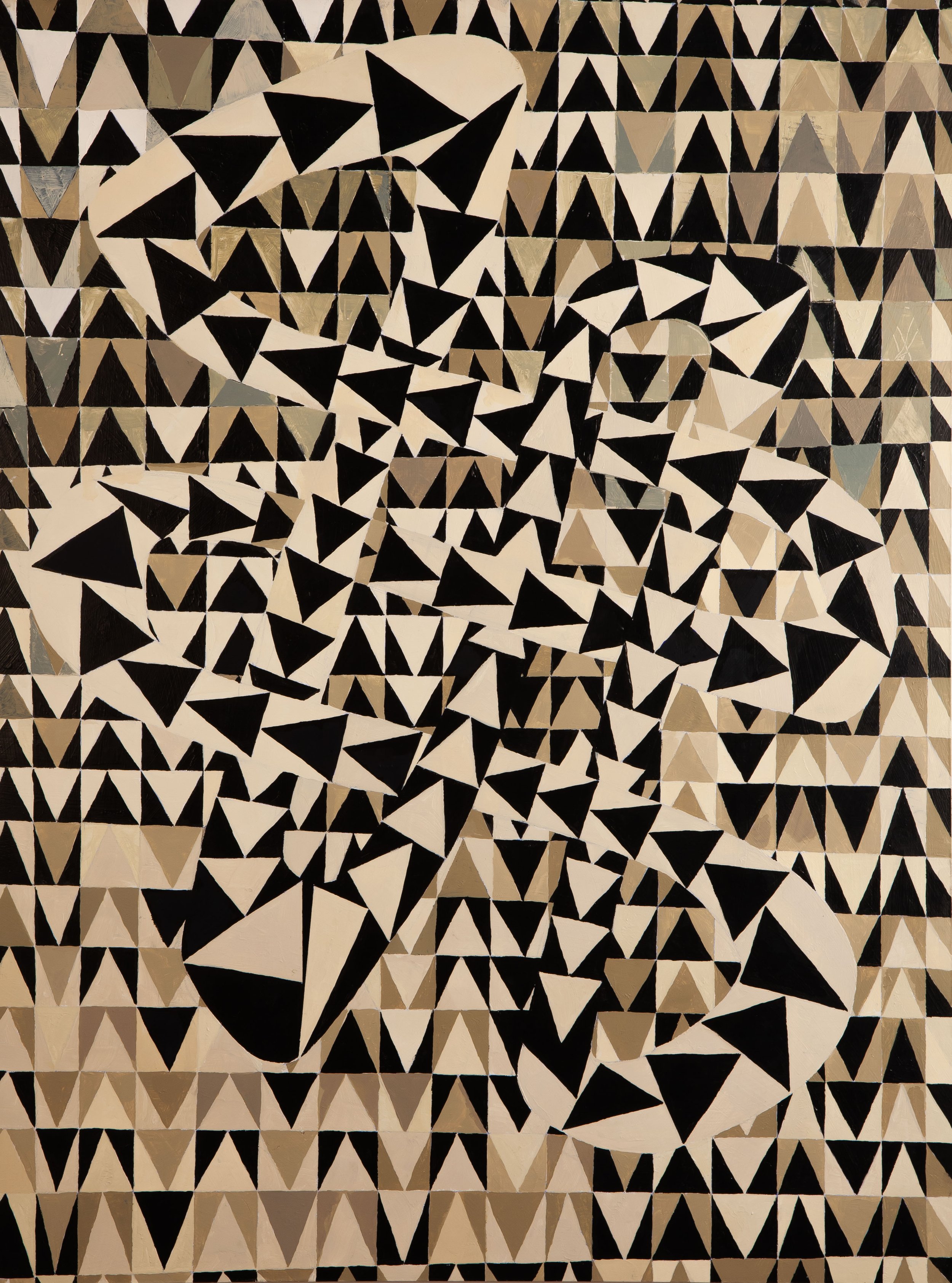

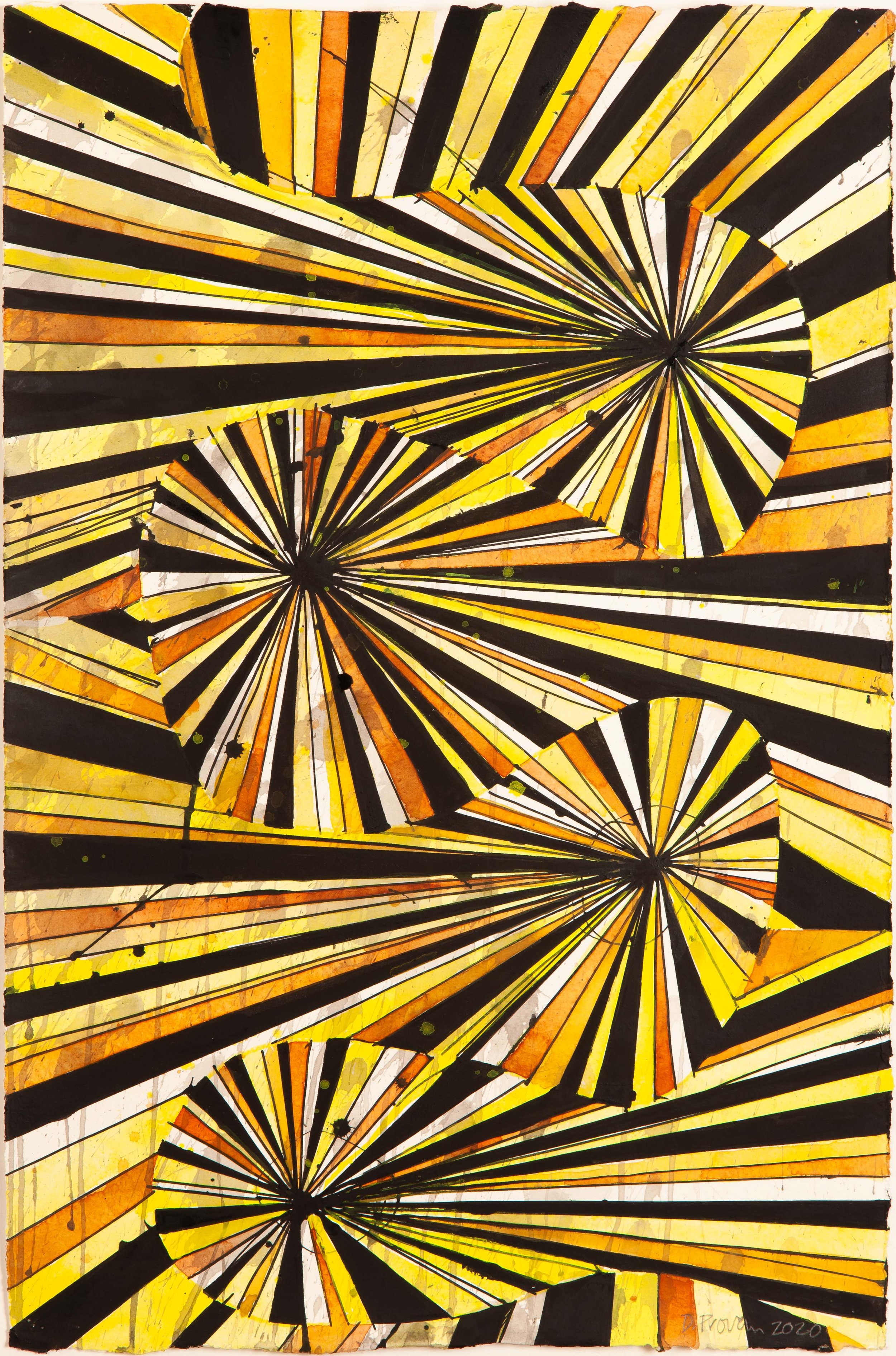

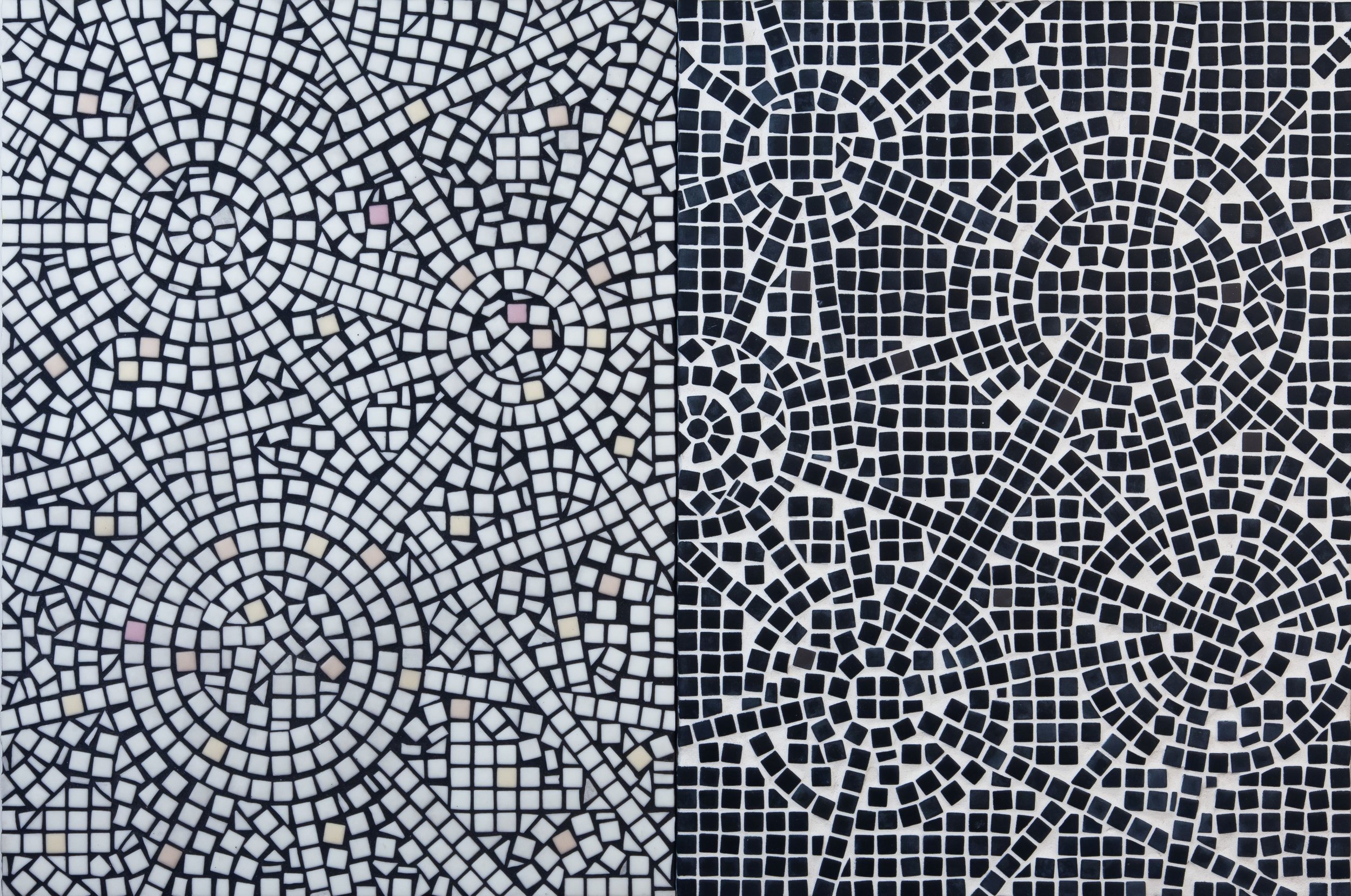

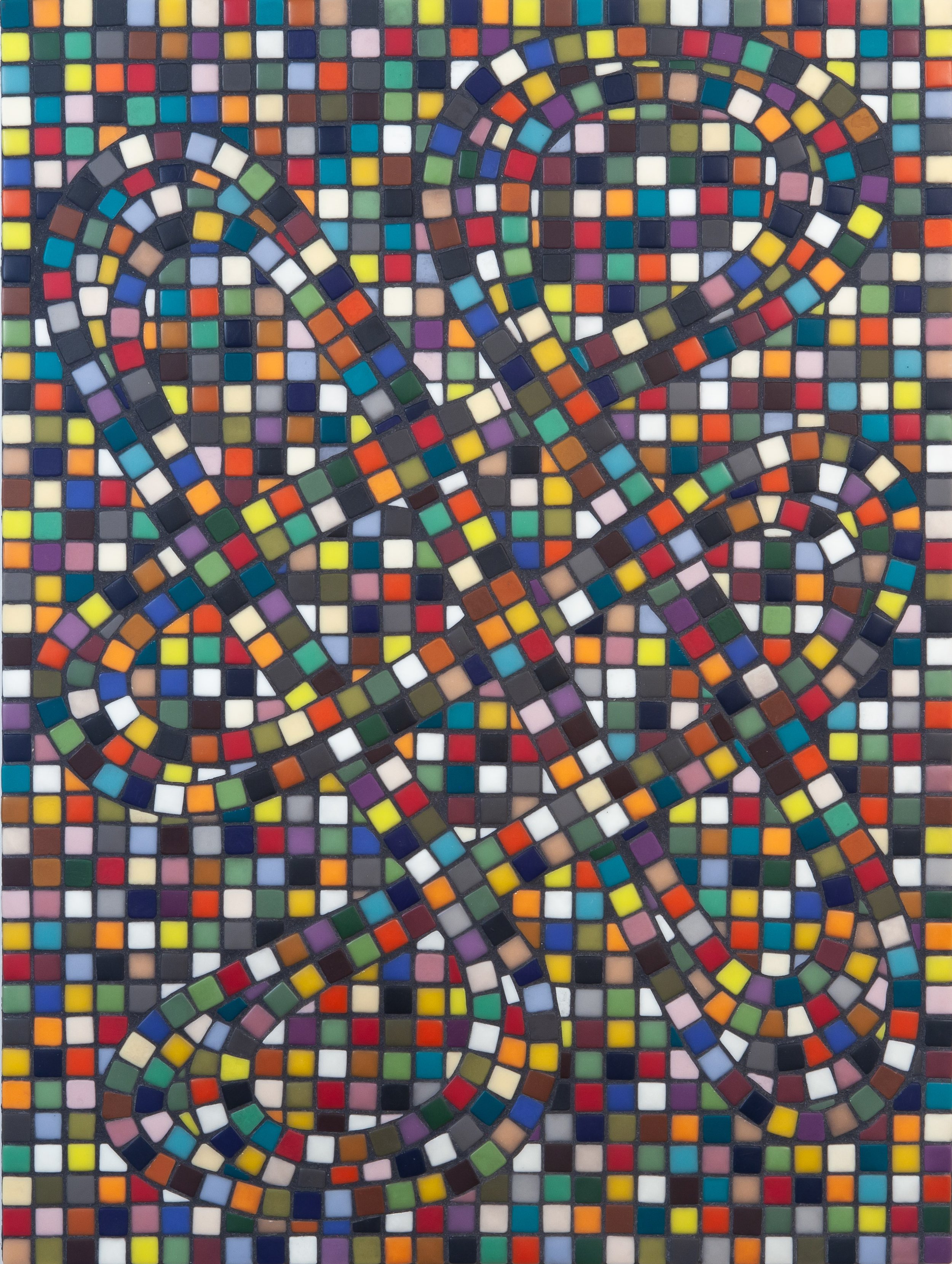

Earlier this year, we were deeply saddened by the loss of a friend and fellow artist, David Provan. His absence is still a shock, and a reminder – as if we needed one – that life is fleeting and unpredictable. Those who knew David appreciated his warmth, humor, and intellect; those familiar with his artwork know him as a brilliant, consummate artist. David was a sculptor who worked in steel, wood, and clay; he was a potter whose vessels are elegant and understated; he was a painter and draftsman, a furniture designer, and, most recently, he was exploring mosaic as a medium for his two-dimensional designs. Everything he made possessed a quality that all artists strive for and therefore rarely achieve, that singular fusion of skill, depth, and effortlessness. David’s work was deeply influenced by his extended travels in Japan, India, and Nepal, where he lived in a monastery in Kathmandu and became an ordained Buddhist monk. His immersion in Eastern philosophy is manifest in all his work, where his innate Western classicism merges with an open-ended Asian aesthetic. It makes for an intriguing dialogue within the work, where the artist implicitly poses the questions, but instead of responding in the classical tradition, David leaves it unresolved and open to interpretation. Indeed, his work seems to eschew a facile reading, leaning into an Eastern tradition that favors subjectivity and mind-bending koans. Many of his sculptures are perforated through to the other side, as though he wants us to see beyond the solidity of Western thought and puncture the illusion of permanence. Imagine the Greek sculptor Praxiteles completing his masterpiece, Hermes and Dionysus, then drilling holes in the marble so you could see clear through. David seems to suggest that the Western paradigm is but one of many options, and the least aligned with science and contemporary thought. A year ago, his solo show, Barely Not Impossible, was on display at Garrison Art Center in the Hudson Valley. (Read my review in Chronogram here). For his artist talk at the gallery, David asked me to lead him in a conversation about his practice and ideas. In preparation, we had a conversation on Zoom where I asked the questions, he responded, and we jumped into some interesting rabbit holes. The following is our conversation, edited for brevity, but true to the spirit of our exchange. It was an honor to take a deep dive into his work, and to have known David Provan as an artist, seeker, and friend.

David Provan