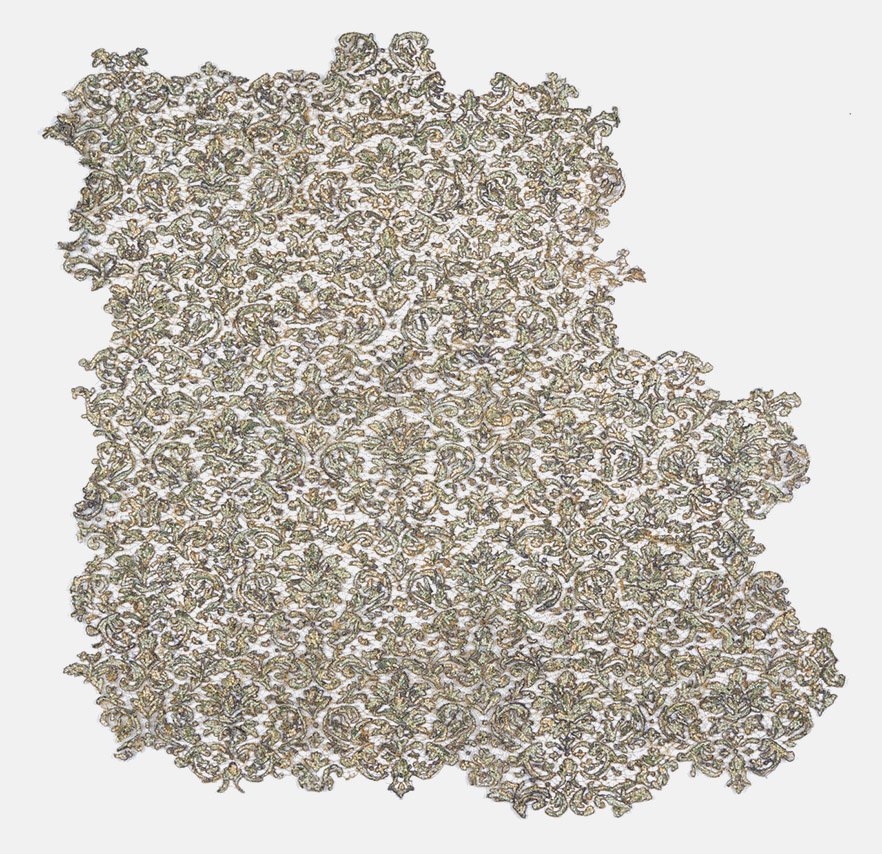

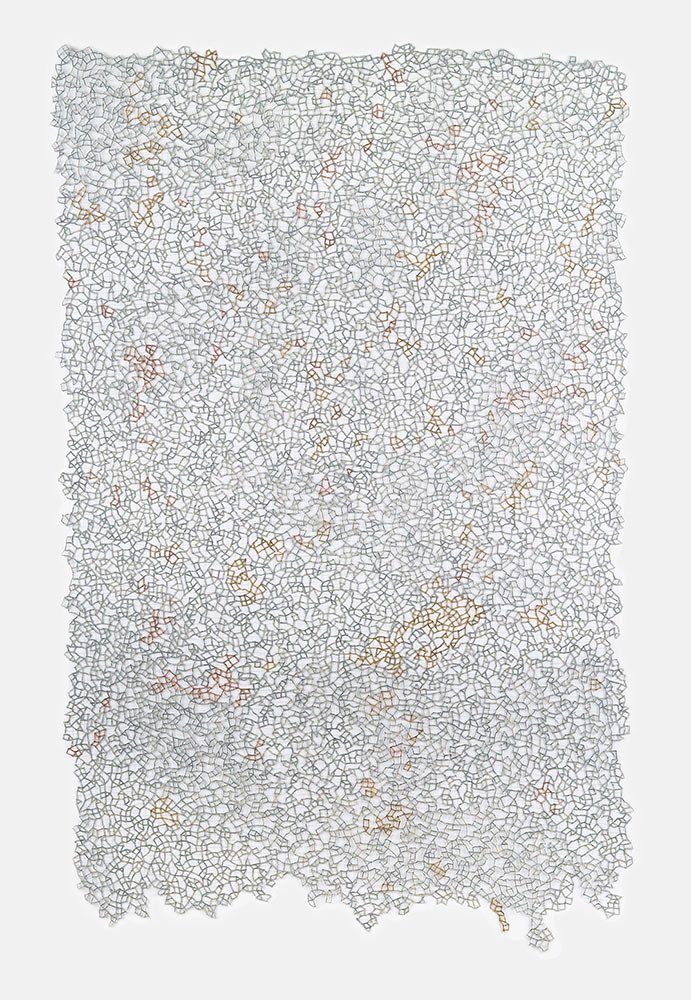

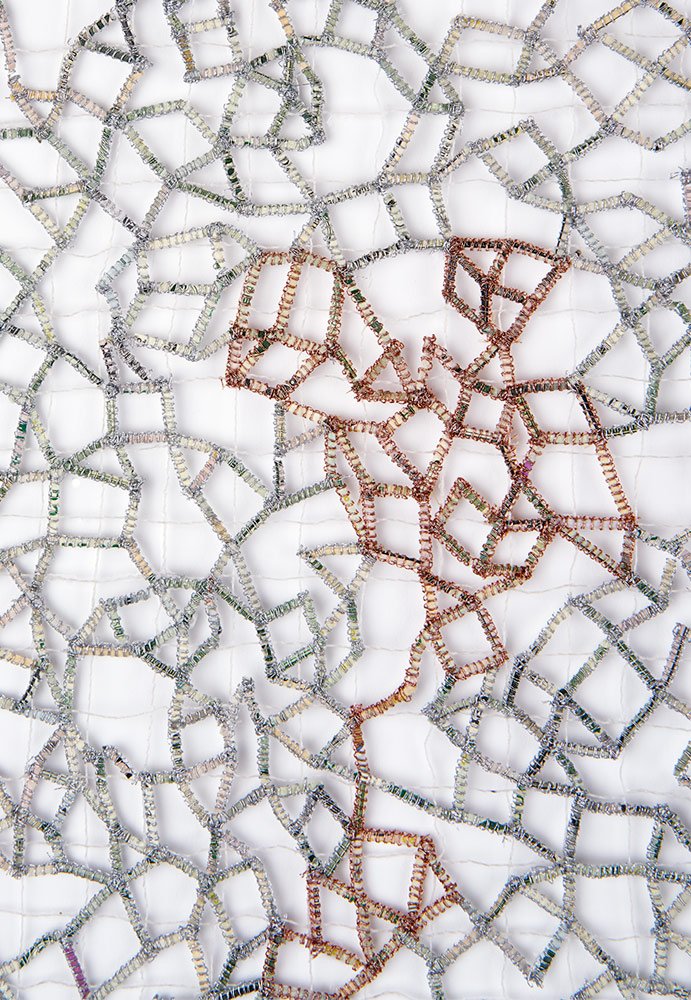

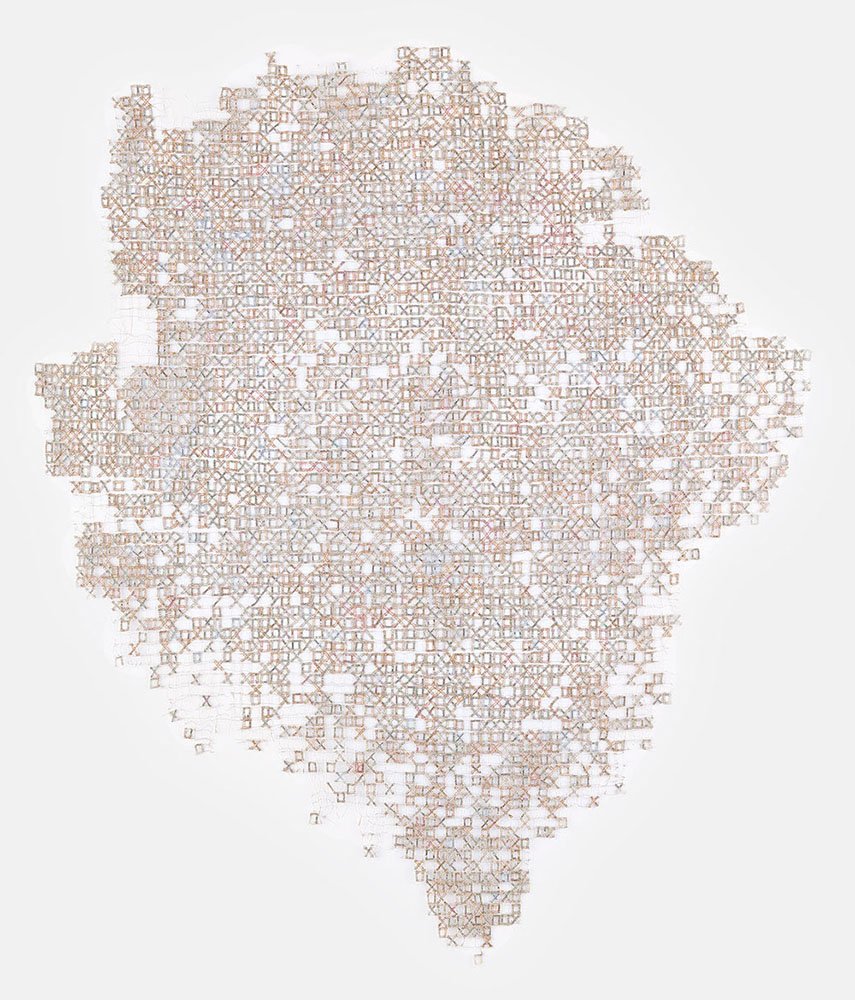

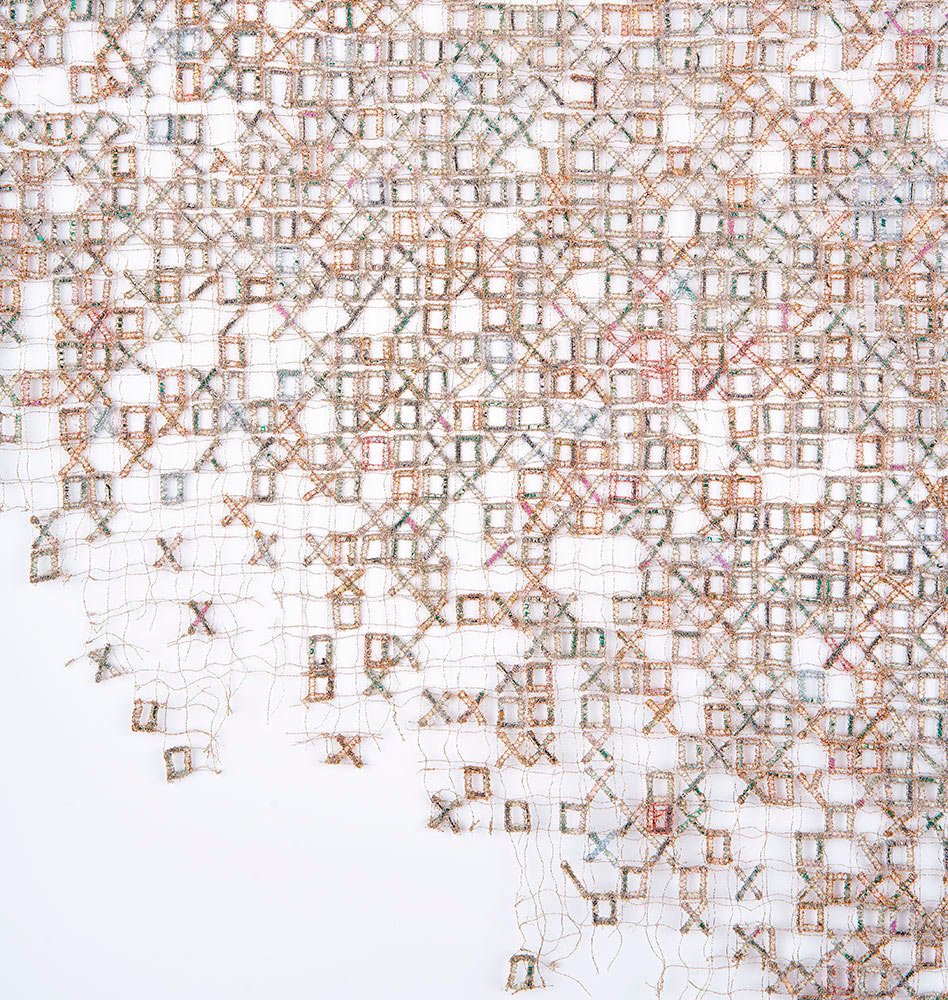

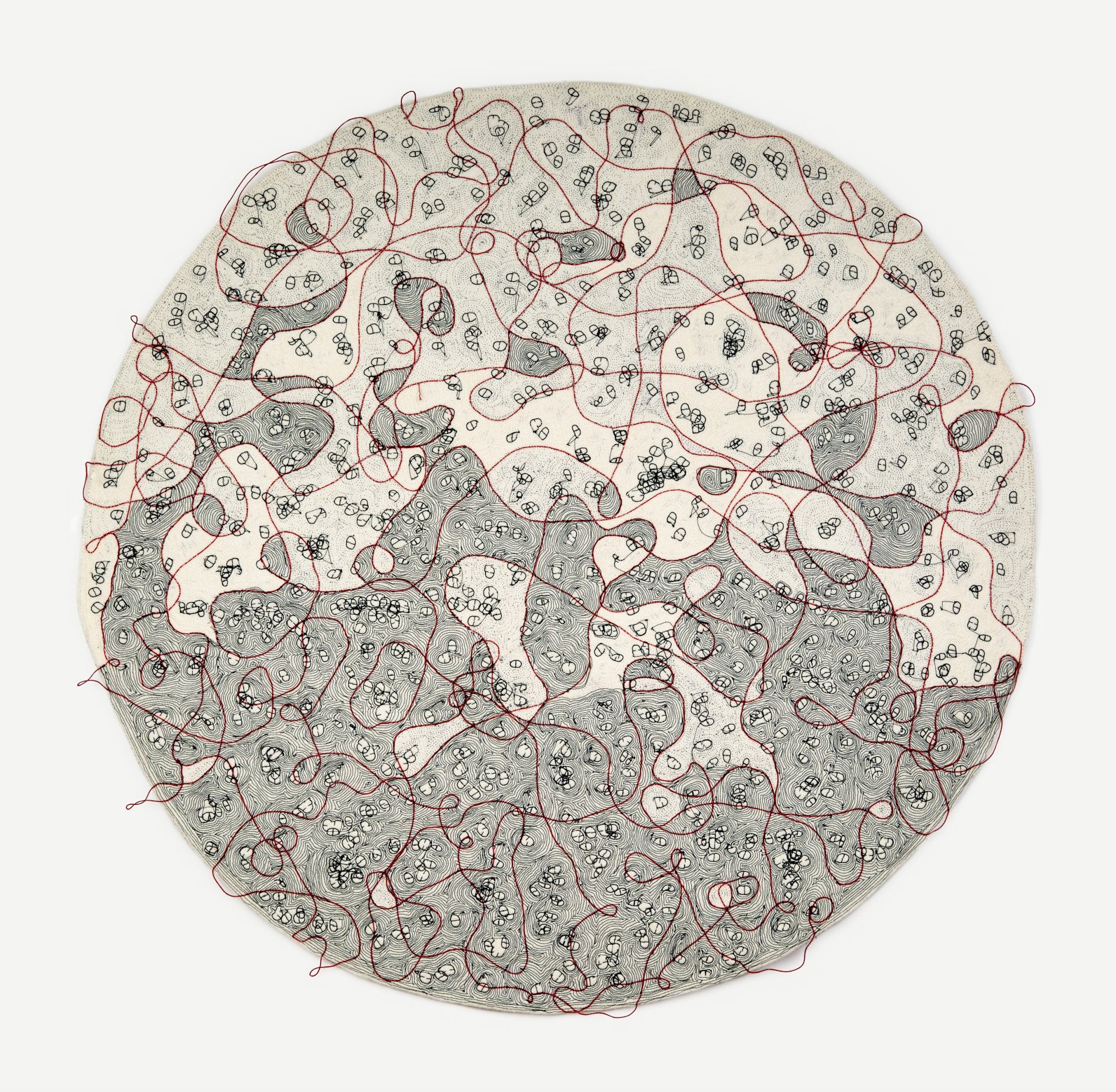

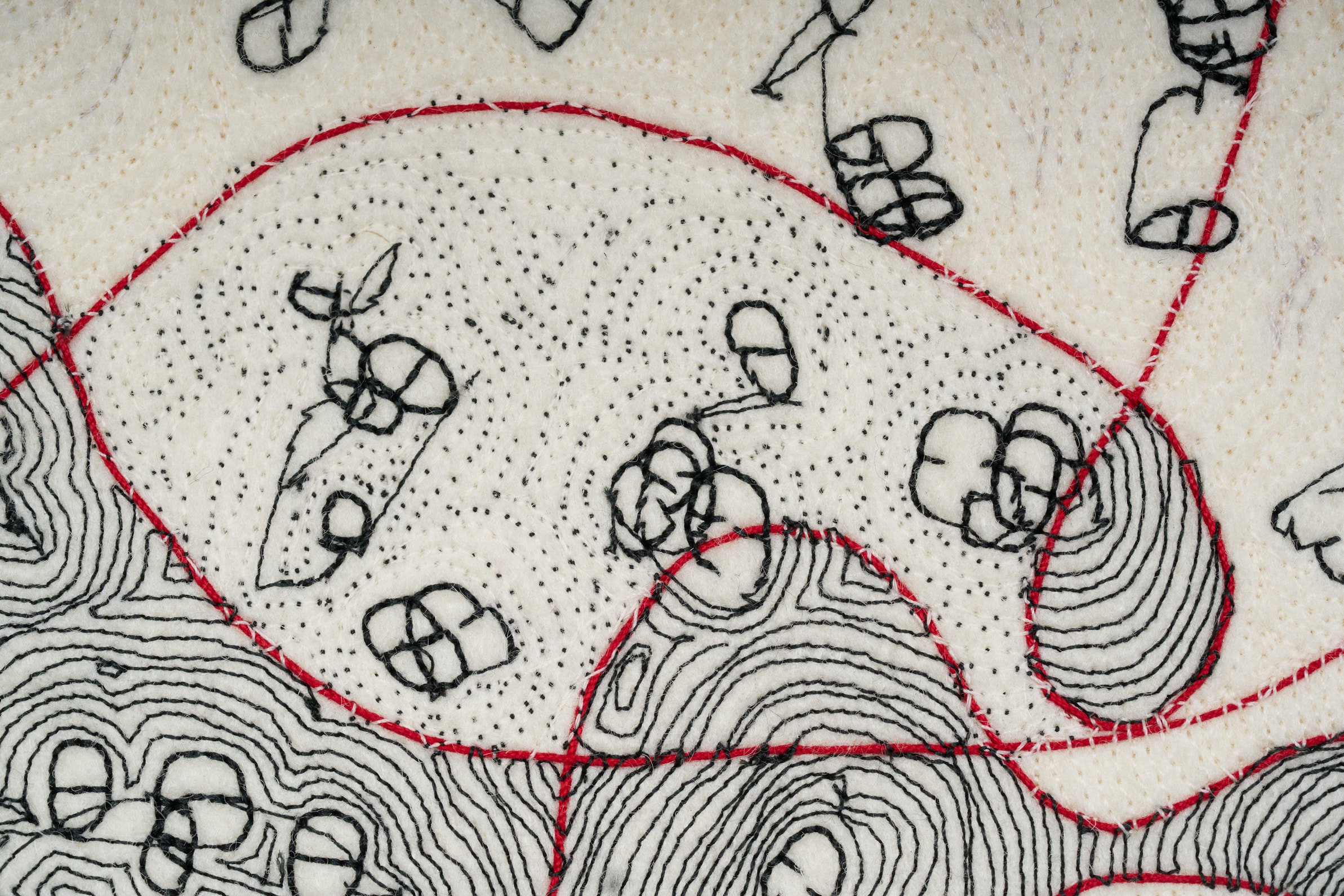

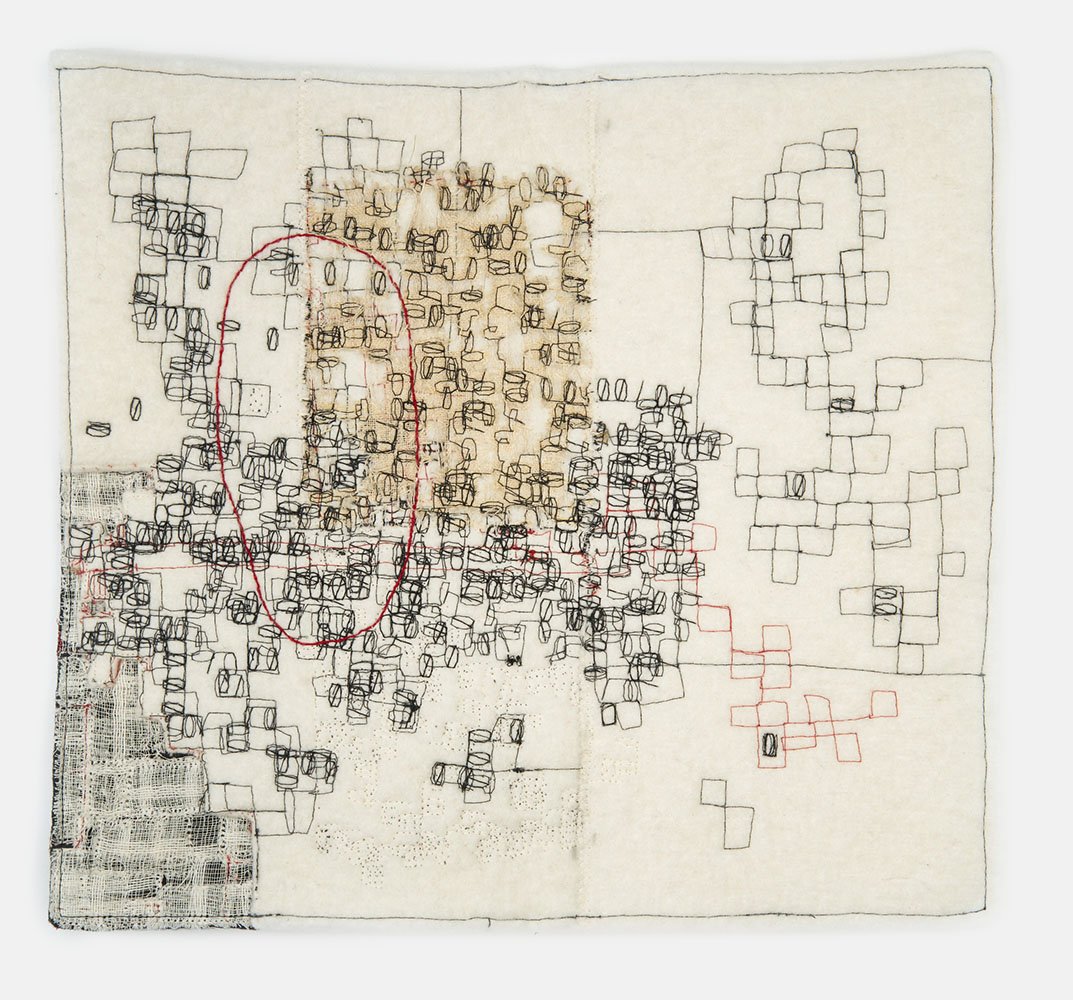

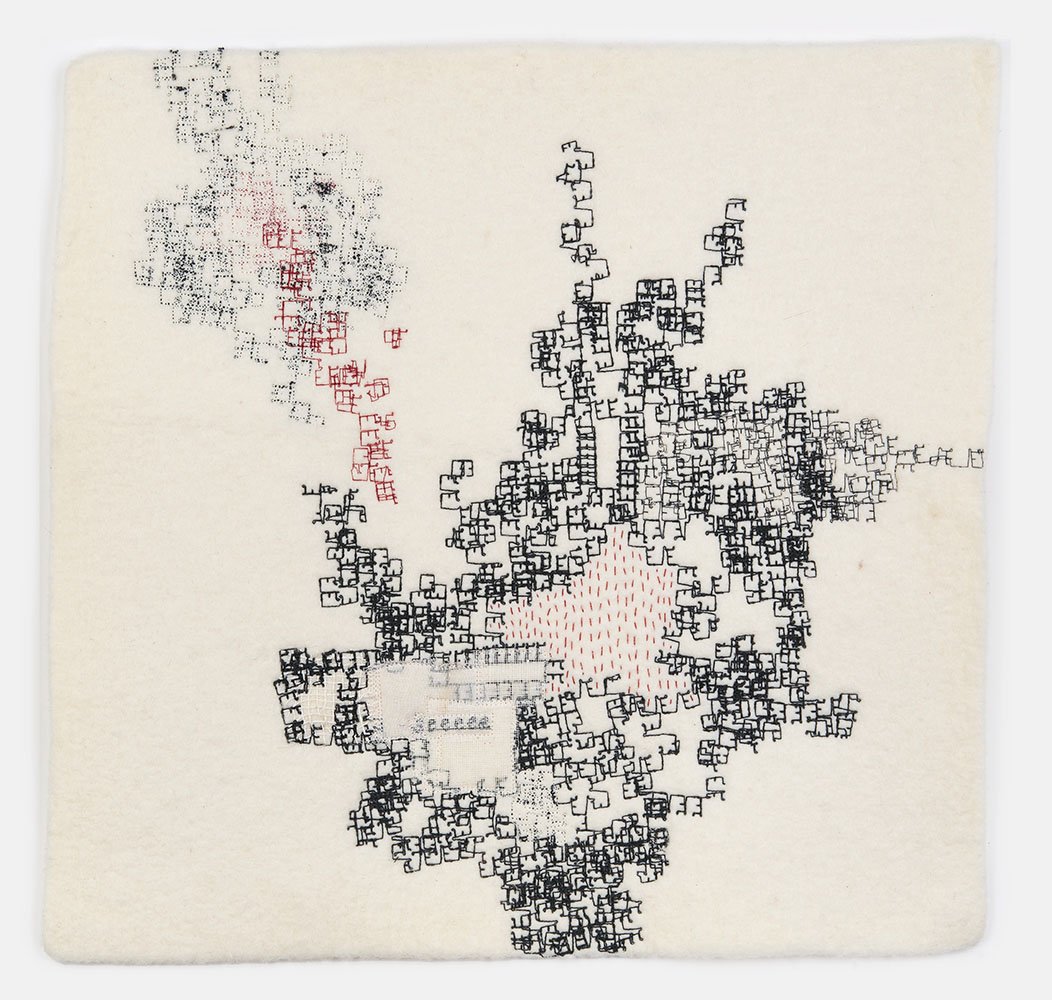

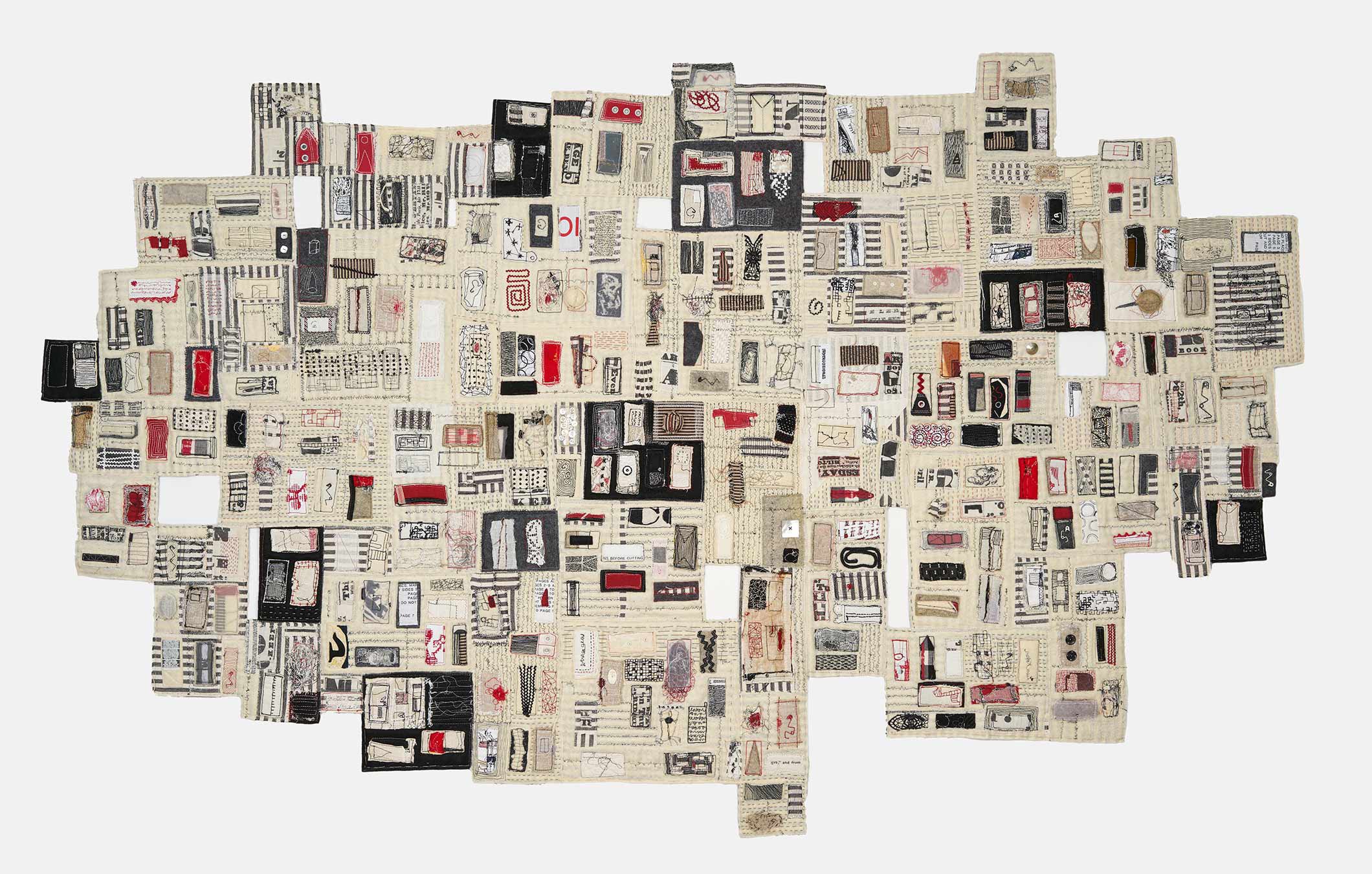

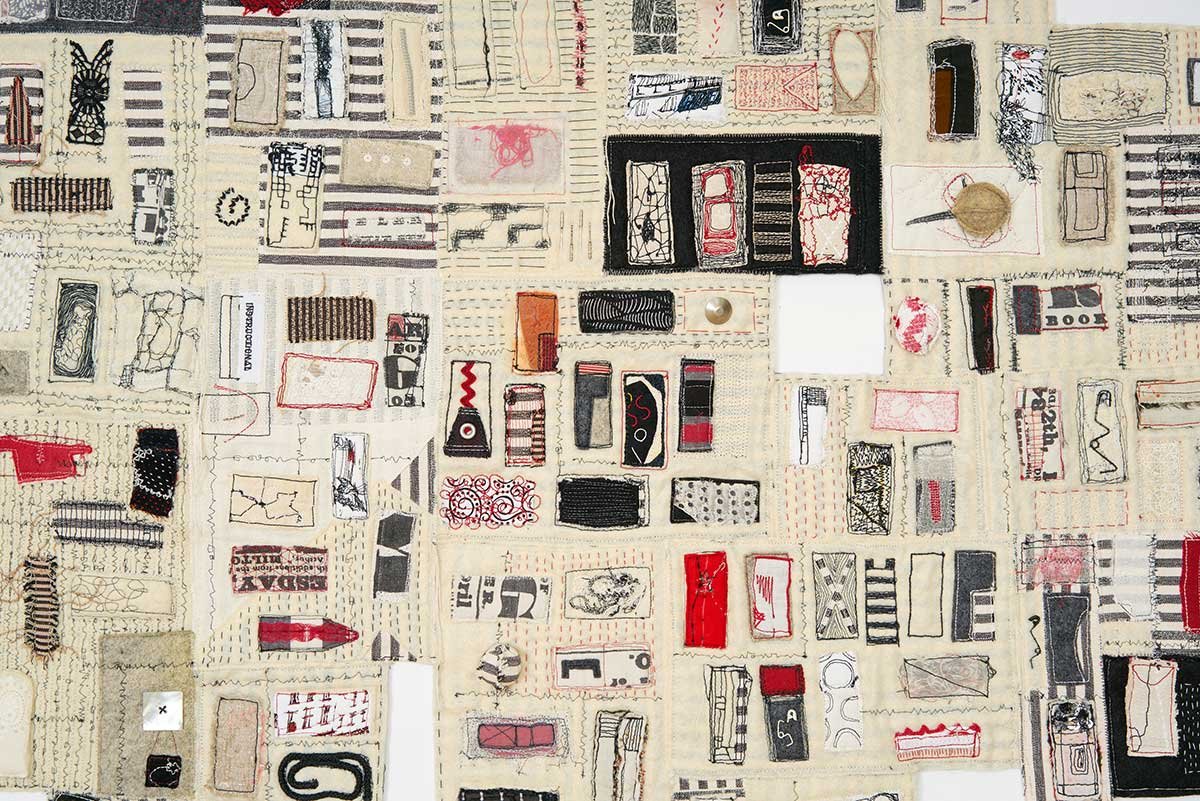

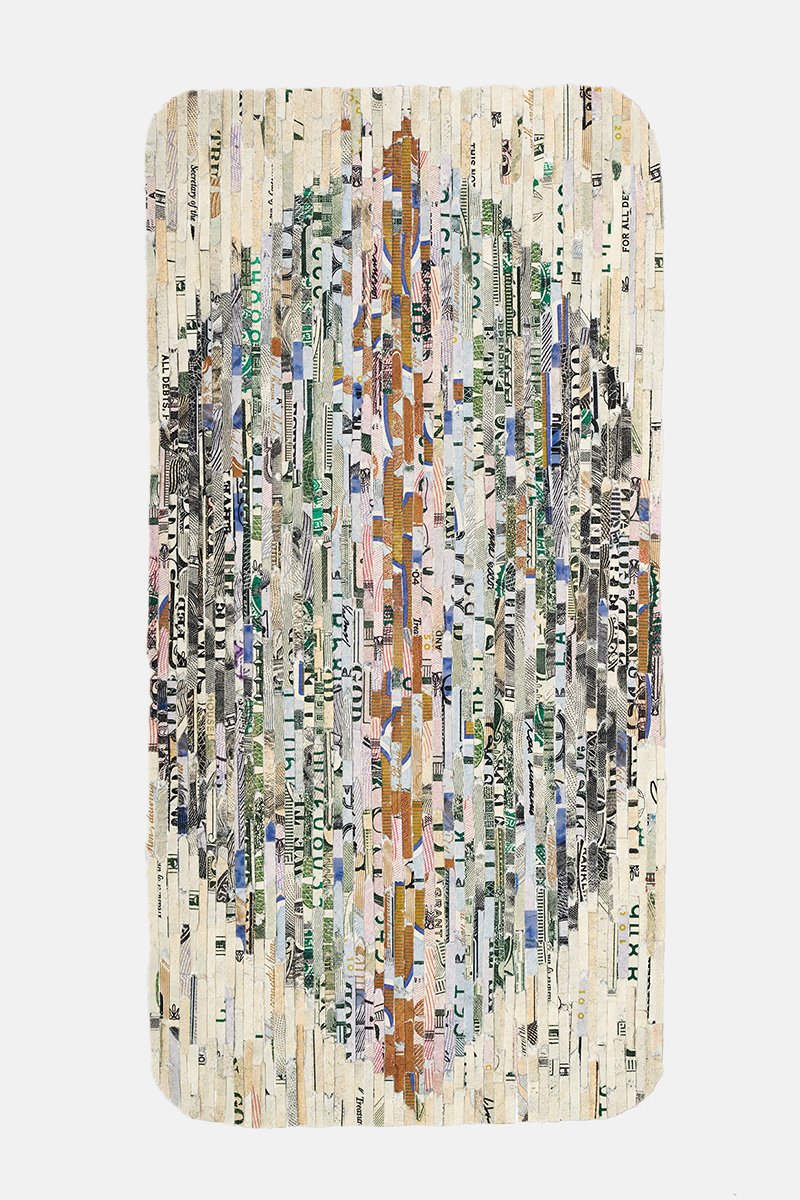

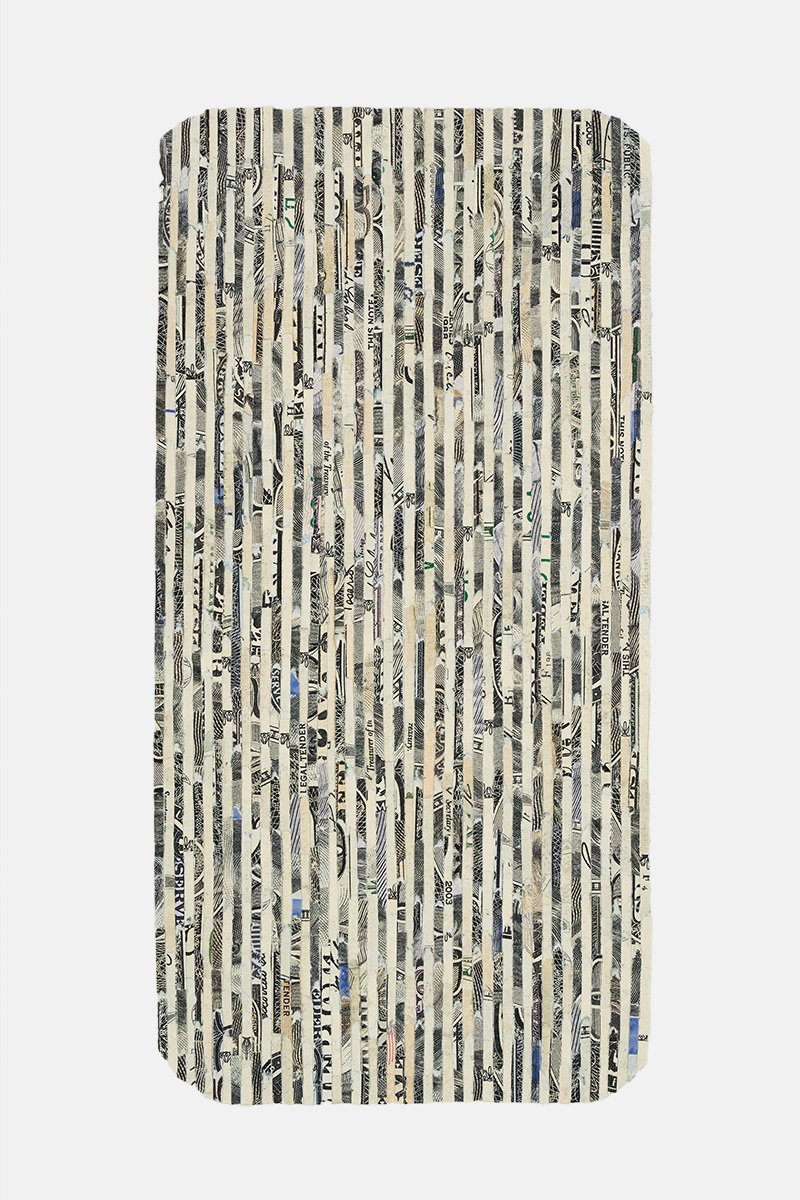

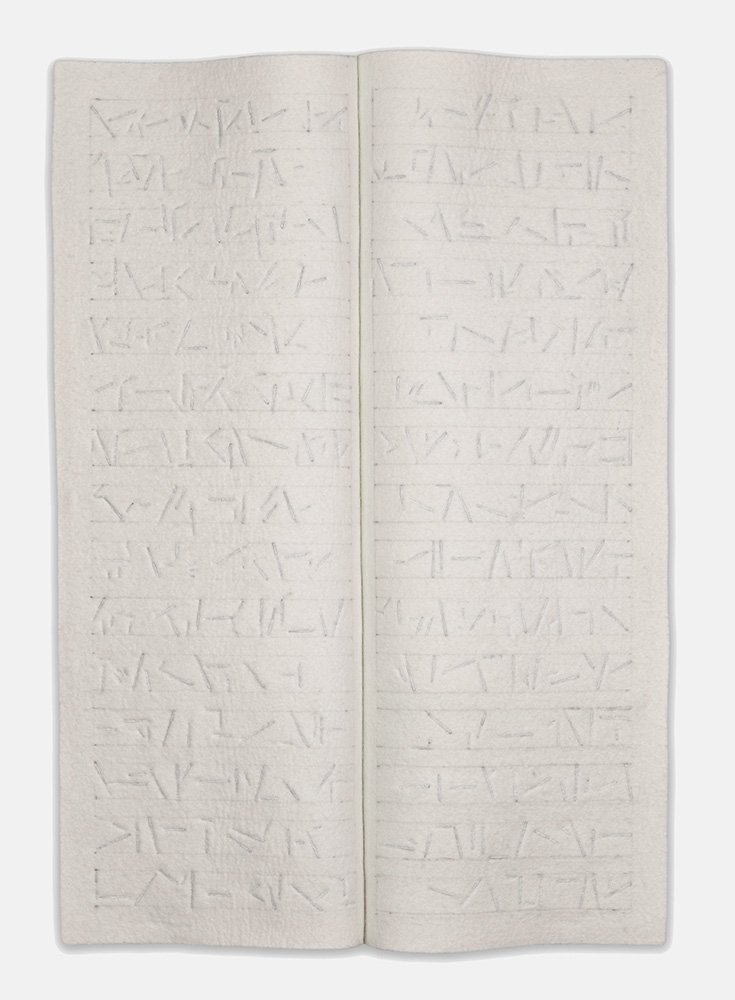

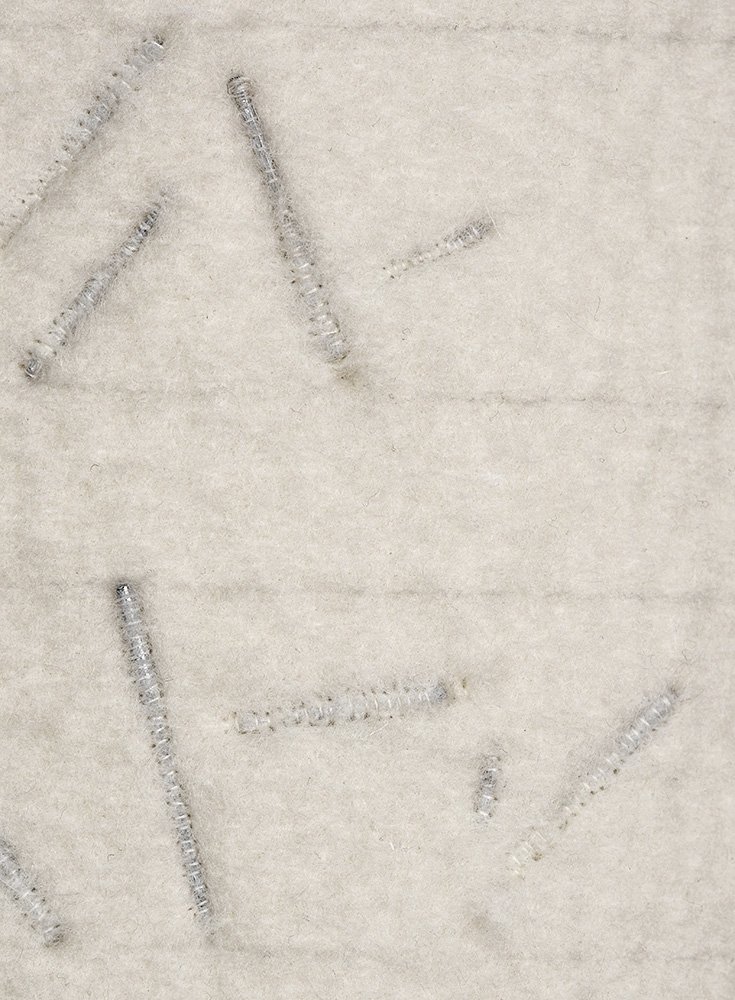

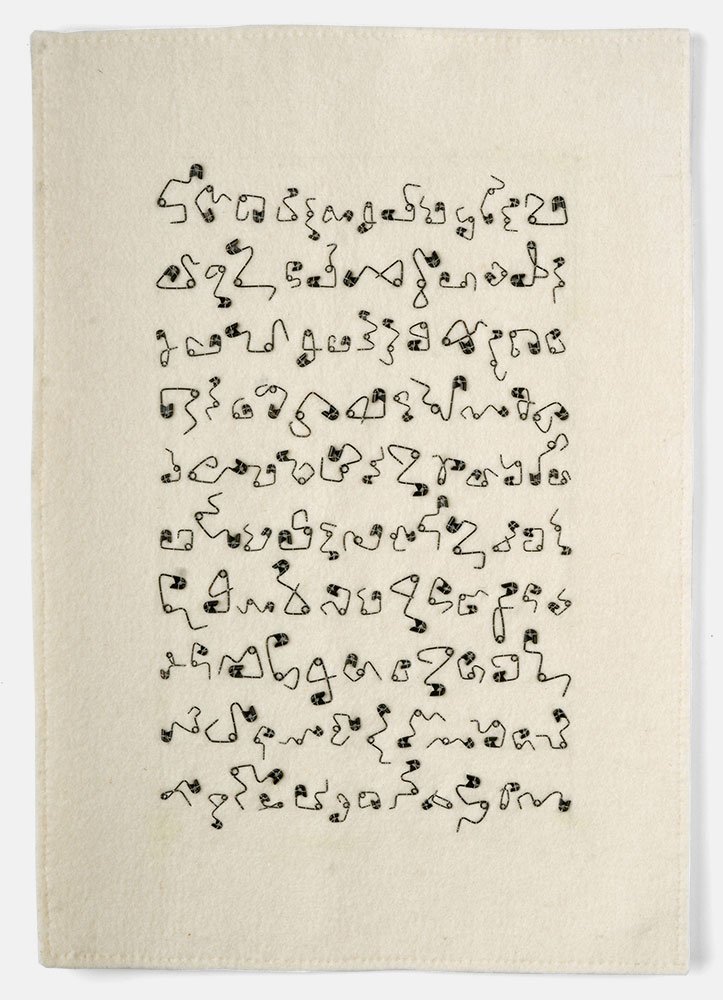

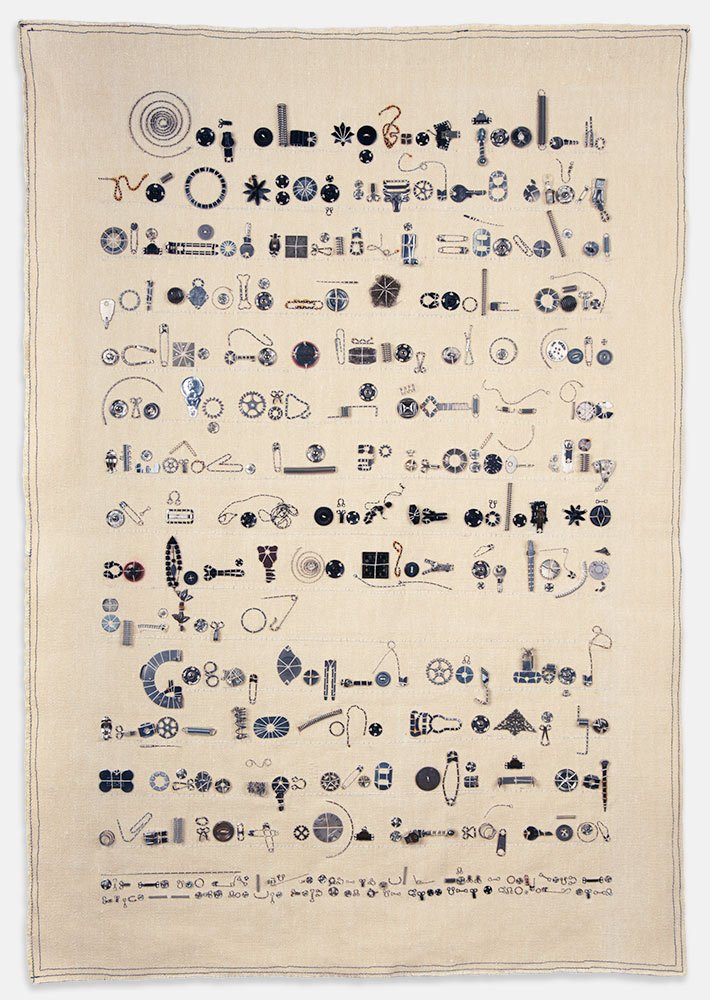

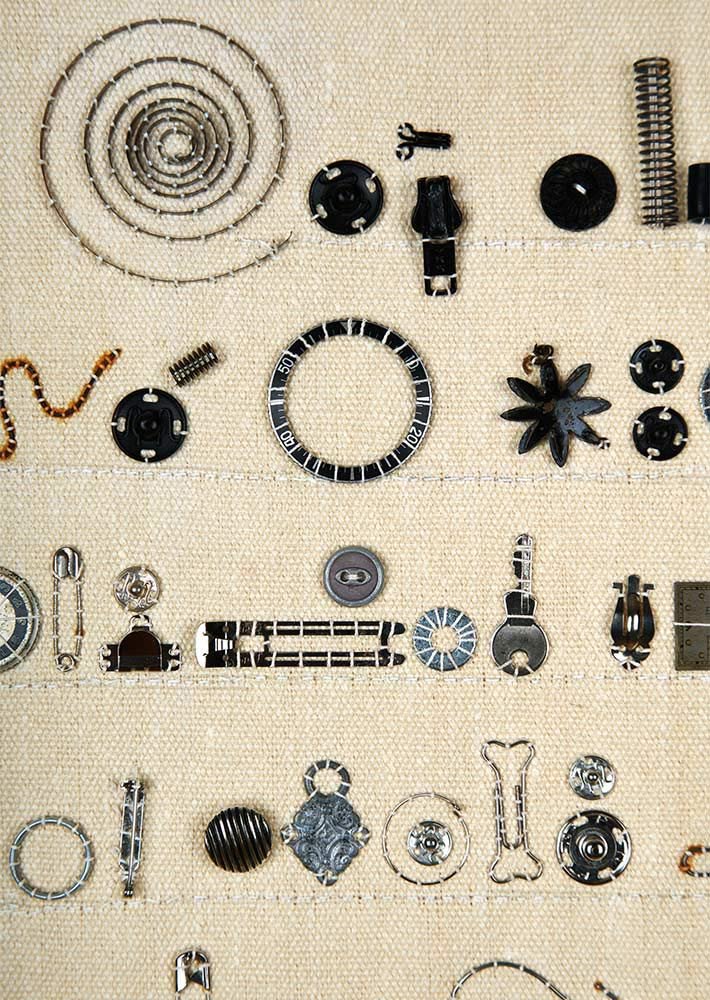

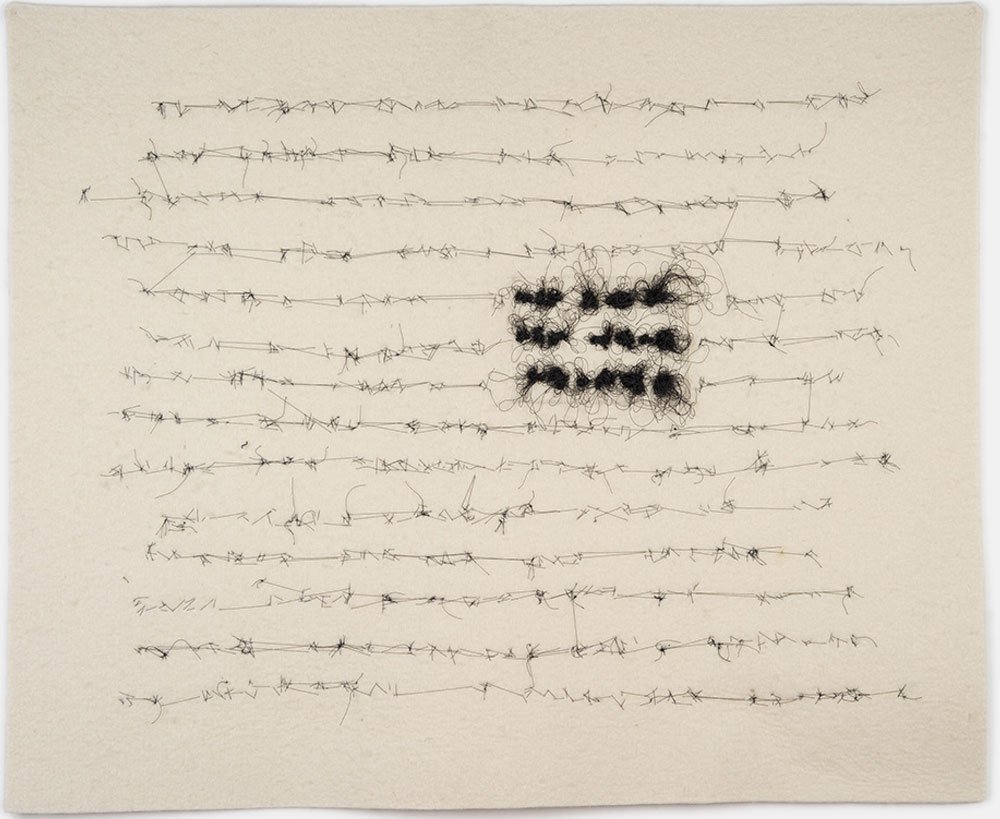

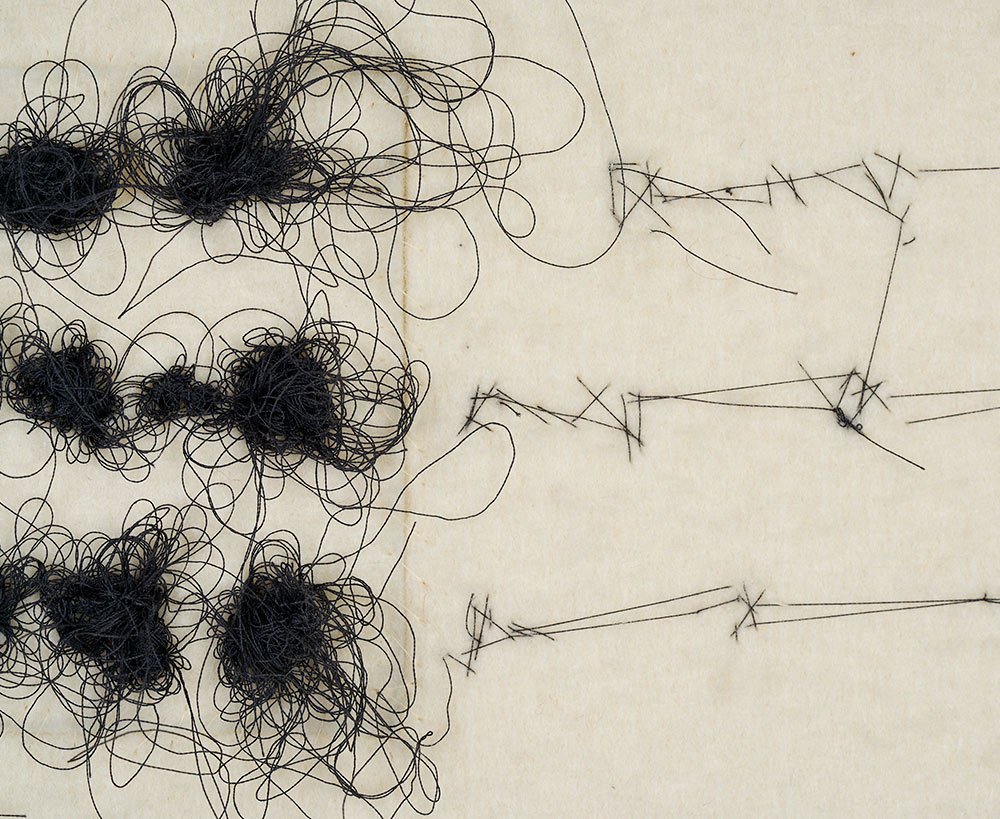

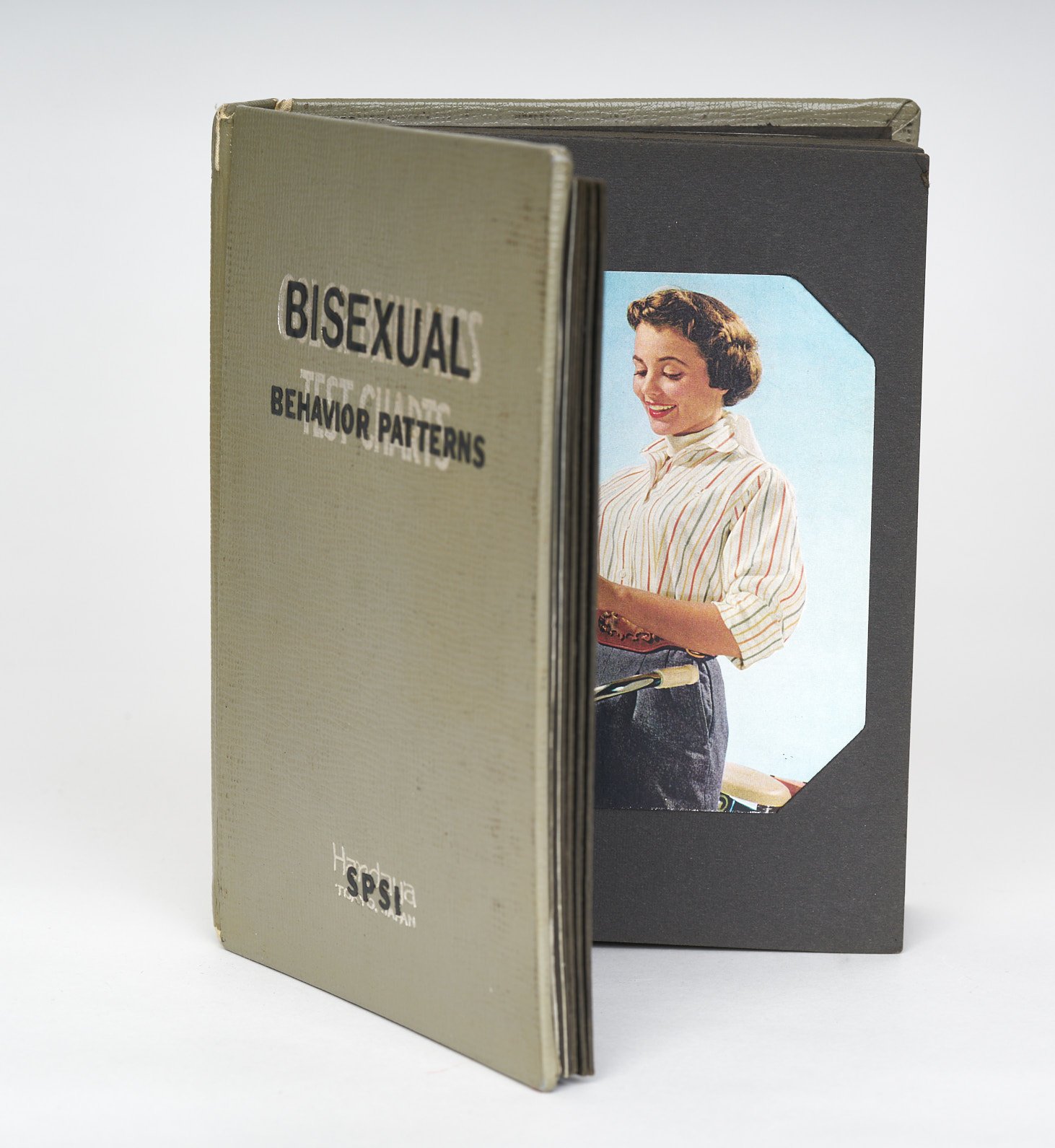

Lisa Kokin works in a variety of materials, from books to buttons to shredded currency. While the materials may derive from many sources, the consistent thread that runs through her work is its connection to sewing and needlework. Kokin comes from a long line of sewists: her Romanian grandmother worked in a New York tie factory at the age of 14, her parents had an upholstery shop on Long Island, and Kokin received her first sewing machine at the age of 9. She describes sewing as a means of attachment and embellishment, and uses it to address social, political, and gender issues that are often at odds with mainstream thinking. Through a labor-intensive studio practice, Kokin expresses her views in a visual language that is at once alluring and tendentious. Indeed, her finely crafted work has an obsessive quality that entices us to move in closer, only to find that the content may be challenging. But Kokin doesn’t shy away from controversial themes. Her current series, Red Line, addresses the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine; her series Lucre, made with shredded money, makes a bold statement about greed and capitalism. Kokin is a master of her craft, but her superpower rests in her ability to challenge the status quo with grace, humor, and unflinching honesty.

Lisa Kokin